Vincent Cochetel has worked for the UNHCR for over 30 years. He spent the first part of his career listening to the horror stories of other people but then his own life became a nightmare. In 1998 when he was working in the Caucasus in southern Russia he was kidnapped and held hostage for 317 days. During Vincent’s captivity he was made to record several ransom demands.

“[I was] handcuffed to a metallic cable that is tied to a bed so that gives me little margin of movement around the bed on one side of the bed. Enough to make four footsteps and you get used to that. It was dark. Darkness was more difficult to cope with than limited freedom of movement. Darkness is something that is oppressive.”

This episode was originally published by UNHCR Refugee Agency

Full Transcript +

Vincent Cochetel Edited Transcript

Melissa Fleming (MF): Most of our colleagues are actually working in the Deep Field in what we call non-family duty stations. That means they’re there alone, they can’t bring their families with them because it’s too dangerous. I have never met such a committed group of staff people working for any organization and I feel like the world doesn’t know them – doesn’t know these people who have sacrificed family life, they have been injured, they have been kidnapped they have taken in the traumas of hundreds of people and they’re extraordinary people. And I just thought the world needs to get to know them.

VINCENT COCHETEL (VC): When you go home at night you think about those stories about the face of the people you talk to, about their emotion. Sometimes you know you are a first person we’ve talked to who has received their stories that each of those stories. So you absorb them. You just absorb absorb absorb and in the middle of the night you have nightmares because you are in those Iranian jails with them.

MF: My name is Melissa Fleming and I’m the spokesperson for the United Nations refugee agency. You know over the years I have met some extraordinary people who have devoted their lives to the cause of serving refugees. What I always wonder is what drives them what keeps them awake at night and what keeps them going. My first guest is Vincent Cochetel. He’s worked for the UNHCR for over 30 years.

VC: So I was handcuffed to a bed, handcuffed to a metal cable that is tied to a bed, so that gives me little margin of movement around a bed. You get used to it. It was dark. Darkness was more difficult to cope with than limited freedom of movement. Darkness is something that is oppressive.

MF: This is Awake at Night.

MF: Welcome to the podcast Vincent.

VC: Thank you.

MF: You started out as a young lawyer. What happened to make you decide to go into working for refugees?

VC: When I was a kid I grew up in in blocks in a project in a small town in France. It was not a very rich area. My parents were not too well-off, all the kids in the block where I leave had a foreign background. And we were going to do the same school and I could see the way society looked at them that they were not treated exactly the same way as me. That shook me at a very early age because for me you know playing soccer with them, I spend all my free time with them. The way people were engaging was different. These were kids of Chilean refugees, French people that had been forced to leave Algeria after the war the liberation war there – people with all other refugee backgrounds – some Portuguese refugees, some descendants of Spanish refugees and we we all grew up in the same area. I’m not sure why my parents ended up living there, but it was quite interesting to be with those kids.

MF: So you chose to study law

VC:: I choose to study law and very quickly for me it was to be about foreigners and probably refugees – and why that? Because I don’t believe that you measure how society comply with human rights by the way it treats its citizens. You measure how society comply with human rights by the way it treats its foreigners and among those foreigners with no rights.

MF: Injustice bothered you. And what about your parents? What did they encourage you or did they want a lawyer who goes and earns lots of money in the corporate field?

VC: Well my parents were both sport teachers so I spent my childhood in stadiums with them, and I think my parents’ life changed in 1968. In France we had a long months of strikes and popular strikes. That was a defining moment for our society, when people stop living the same way than before and start raising questions. And then my parents got really involved socially, more with homeless people, quickly realized that you cannot change the big things. You don’t change homelessness as a phenomenon. It’s too difficult. But you can help a few people you can change a few life.

MF: You know most people I think I’ve seen in Europe have never met a refugee. So you grew up among refugees and you decided to work for refugees. What was your first job in this field?

VC: My first job with UNHCR it was in Turkey. I was sent to interview asylum seeker a bit like a machine. We had groups of asylum seekers from Iran and from Iraq brought by the Turkish police to our office in Ankara, and we had a very tiny office and we were two officers down there. We had about 20 people, 20 every day, they were brought in handcuffs by the Turkish police and we had to interview them on make a decision as to whether they were refugees or whether they were economic migrants coming looking for a better future.

MF: So just so our listeners understand UNHCR had the role of taking over the asylum interviews on behalf of the Turkish government?

VC: Exactly there are many places in the world, more than 60 countries, where governments don’t take this sort of decision and UNHCR has to take those sort of decisions.

MF: OK so the backdrop was the Iranian revolution and many people fleeing and you’re right and you are what 22?

VC: Yeah I was 23 years old lacking experience never had been confronted to that sort of situation where people talk to you about execution, prison, torture, trying to distinguish people who were genuinely suffered human rights violations from people who had been committing human rights violations

MF: These experiences as an officer who hears asylum cases and claims it can be very traumatic. There is a syndrome called secondary trauma. I mean did you feel that. What was it like when you went home at night?

VC: When when you go home at night you think about those stories about the faces of the people you talked to, about their emotions. Sometime you know you are the first person who has talked to them who has received their stories. Sometimes the father would not talk in front of his children, the husband nor the wife would not talk in the presence of the other spouse would not share with you their story. So you are the recipient of a lot of horror and you have to try to make sense of that you understand the whole story before taking a decision, that each of those stories somehow you absorbed them and unless you have good counselling and in those days we did not have anything like that, you just absorb, absorb, absorb, and in the middle of the night you have nightmares because you are, you are in those Iranian jails with them.

MF: And nevertheless you continue this work at UNHCR.

VC: I continued because I could see with my colleagues that we couldn’t change anything you know, Iran was bleeding all sorts of people were leaving the country for good or bad reasons. You had a war with Iraq at that stage, you had the Iraqis also leaving, and you realise you can’t stop those wars. I mean you have absolutely no power to stop anything like that, but you know this individual in front of you, you may be able to to help that person, you may be able to save that person.

MF: So you can’t stop the wars but you can help the victims.

VC: Exactly. And that’s a driving and very compelling force. No absolutely not that many jobs like that where you can see the impact of what you are doing.

MF: But hearing all those horrors. How did that change your outlook towards the world and humanity?

VC: Well I mean do you see the dark side of the human being you see also the resilience the courage of people. But professionally it’s difficult because you know you then you have to be attentive to your spouse to play with your kids and sometime you want to, you close, you don’t talk too much about your work because what you want to share – the contrast is yes – you don’t want to transfer those trauma to people you love but then you keep everything.

MF: You spent the first part of your your career listening to the horror stories of other people but then your life your own life became a nightmare. In 1998 when you were working in the Caucasus in southern Russia close to Chechnya a region that was torn apart by a separatist insurgency – you yourself were kidnapped.

VC: I was the head of corporation for the North Caucasus for the refugee agency and this region was black with several conflict. And at the same time that you had this conflict you had criminal elements cross fertilizing with militant groups and hostage taking became a business at that time. A few foreigners that were in the North Caucasus were humanitarian aid workers and several got abducted many released against ransom and some others disappeared – some were killed.

MF: You weren’t worried that this would help you.

VC: Well we knew there was a risk we were taking all sorts of precaution in terms of security. We were I think quite careful. Many humanitarian aid workers had left the region and somehow maybe we thought we were safe. We were operating quite far off from Chechnya. So we saw that we were out of reach for that sort of threat.

MF: What happened on that day?

VC: So one day you know one day I came back late. I had a big boss coming from Moscow for some meetings so I took him out for dinner to a restaurant, brought him back to his hotel. I was not followed, but when I arrived to my flat with my driver who was also my bodyguard, I start to open and opened the door of my flat – some three men with mask and fully armed came down from the floor above me, and they asked us to put our hands up and get into to the flat and then they searched us, they separated us and he took me to another room and asked me to kneel down in front of my fridge. There was one guy put a gun with a silencer against my neck. At that time I thought he would be some sort of contract killing and must have had antagonized load of people not awarding contracts. So I thought okay that’s that’s it. That’s that’s the way it ends. And then they blindfolded me took me downstairs and put me in a car, a trunk of car, and transfer me from car to car and after three days I was in Chechnya in a basement.

MF: You were in the trunk of a car for three days.

VC: You feel you’re not going to breathe. You don’t feel your legs after some time because it’s blood circulation which was bad. You smell the fumes of the car you feel every bump off the road. I tried to keep some notions of the time, calculated more or less 3/4 minutes by each song that they were playing on a tape loudly in the car and tried to keep a sense of direction – the car goes left it goes right – we drive 200 metres here, there. So I had some idea of the direction more or less where we were taking because I’d been living in that area for more than two years. But then I got I got lost – I got a lost sense of direction – I kept some sense of time. I don’t think I slept much over those three days.

MF: It must’ve been absolutely frightening

VC: Very frightening. And we know also from training we’re a bit trained for this sort of event but not on such a length of time you know three days in the trunk. It’s not like having a sand bag on your face for one hour. It’s it’s a long time. You know that as long as they have not brought you to a place of detention, this is a dangerous phase, because those guys can be stopped on the way things can go wrong. So you don’t question order and you just wait for the next step to take place and then I was transferred from one group to another. Some spoke Osset others spoke Ingush and then the last group spoke Chechen and I realize after some time I was in Chechnya.

MF: And where did they put you?

VC: They put me for the first three days. I was in a room, reasonably well treated and I was considered to be a guest by my host. Had two guards with me all the time. Got some good food for three days. After three days the treatment changed. They put me to a cellar. So I was handcuffed to a bed.

MF: You were handcuffed to a bed?

VC: Yeah, handcuffed to a metallic cable that he’s tied to a bed so that gives me little margin of movement around the bed on one side of the bed. Enough to make for four footstep and you get used to that.

MF: It was dark

VC: It was dark. Darkness was more difficult to cope with than limited freedom of movement. Darkness is something that is oppressive. Because after some time the brain starts creating colours, images some weird thing weird thoughts

VC: How did you work with your mind which was going in those kinds of directions?

VC: So I try not to think and that’s difficult for me or for anyone try not to think because when you think you don’t think very positively, you think about, you know, the what if that can go wrong. So I tried to keep the mind focus on physical exercise on all sorts of memorization games is a bit of praying a bit of translation games always try to keep the mind busy on something else than than just thinking about what can happen.

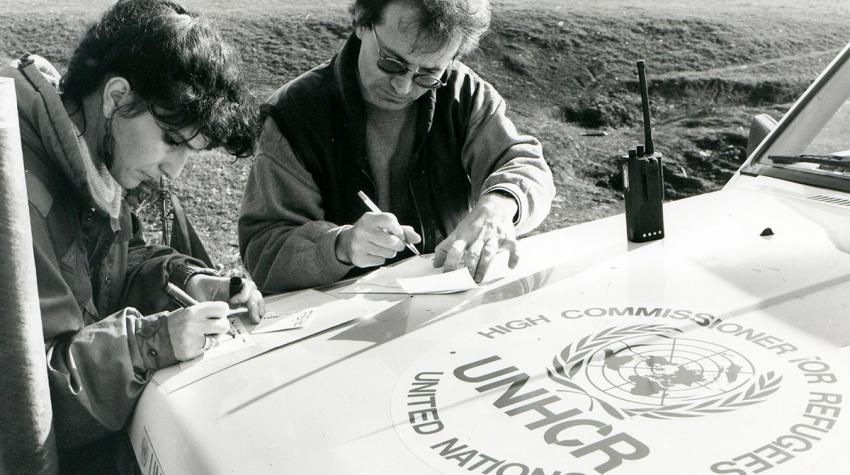

MF: During Vincent’s captivity he was made by his captors to record several ransom demands. On these recordings you see him stating the date and asking for help in Russian. The first videos you can see he’s clean shaven, but later he has a thick beard. He’s in a dark room lit only by candlelight, and you can sometimes barely make him out.

MF: You were held for 317 days like that in that dark basement. You were given food I believe only once a day. And that was the only time you had any light the light of a candle. Yeah. What do you think about when you think about a candle?

VC: Well I love candles. I have many candles in my place I like candles.

MF: So that was 15 minutes?

VC: 15 minutes of quiet time. Normally sometimes an opportunity to engage a bit with the guard. Sometimes the guard would stay with me the 15 minutes. Also use that time to share the piece of bread I was getting. So I would normally cut it in half so I would have two meals a day, try to save a bit for the other part of the day. The candle always the hope of better days. I’d been doing a lot of volunteer work with Amnesty International before and candle was our symbol and I remember selling that on markets. So that was there was something that kept that hope of life alive.

VC: These guards were your captors. You engage with them sometimes. What kind of relationship did you have with them?

VC: Well some of them the dialogue was was violence. Some of them were silent, some of them were a bit more talkative. Soldiers of fortune, they could have worked for in any criminal group, any militant group. When they would speak normally their favorite themes were weapons, woman, car. Not much more than that. Occasionally there was one or two guards that talk about classic French literature. Somehow in the Soviet days you could not get the modern literature, but they all knew very well their classics were sort of interesting discussion. Totally surreal with guards talking about literature, me trying to argue something with limited Russian vocabulary. But it was still interesting encounter. But some of the guards were brutal. They were, either because they were drunk or because they were sadistic or some time because they were – didn’t know how to handle me. And some time because I was not nice to them. There were moments where I let it go into the frustration or was was myself aggressive with them.

MF: What surprised you about yourself?

VC: Well I think first you have to be confronted to a very difficult moment in life to find out that you have so many resources and needs. It’s terrible to consider that you need accident in life to to know that. For some people it can be a car accident a long illness the loss of a close friend. Others might be an abduction in my case, but it’s amazing the resource that we have and that we don’t use because we can adapt and this is what refugees have taught me over, over life people adapt. People are resilient, people can go through very very dark moments, but then with the hope that some something better will happen. And so you can cope with violence you can cope with the pressure. But there is no there is no bottom. You know some people set artificial threshold and say I won’t do this. I won’t accept that. If you set artificial threshold I think you don’t survive.

MF: Vincent was rescued in a gun battle between his captors and Russian special forces – who filmed the whole operation. It took just five minutes – but for Vincent it felt far longer.

VC: I was woken up in the morning by the group holding me [they] blindfolded me handcuffed me in the back. I was taken to a car blindfold, removed put back transferred from different car driving in a convoy of brand new four wheel drive cars. Three o’clock in the morning, heavily armed guards all around me, and there is not much talking in the car. And I’m handed over to a last group – a small white Jeep – it’s three o’clock in the morning that I will know after – and they blindfolded me again they put me in the middle of the back seat.

That car drives into no man’s land off road and all of a sudden it’s like in a bad movie there is shooting outside, windows being smashed, one body falling on me on my left hand side and emptiness on the right hand side. I feel the air outside the door is open so I just dive, fall on the ground, take cover under the back rear tyre of the car. And they’re shooting around. I’m hearing “Where is the hostage where’s the hostage?” After some time I say I’m here. Someone pull me ask me to kneel down. I don’t know whether these are the hostage keepers, is it another group stealing me? And all of a sudden someone carried by two, they ask me to walk I can’t walk I don’t feel my legs, think I’m trembling. And these two guys they pull me and drag me about two 300 meters throw me into another car. And there I hurt my head on a helmet. It was on the floor of the car and I know I’m with the Russian forces because the Chechen don’t wear helmets. And we drive drive drives and we go to an undercover operational center of special Russian forces.

MF: When Vincent was rescued it made global news. TV channels showed him thin and pale, falling into the arms of his family.

French television broadcast Vincent’s first phone call to his family after 11 long months.

MF: You came back extremely thin and probably traumatized but you decided that you wanted to return to the work that you were previously doing for UNHCR and serve refugees. Why?

VC: Many colleagues said you know, you have enough. Why don’t you do something else? Not my family but colleagues. Why don’t you do something else? You know people will understand your still young, you can do something else. Then I say no. If I stop now what it means my kidnappers would have won, they would have taken my soul, my humanity, my purpose in life. So I’m not going to stop now. I’m not gonna stop. No I got turned into something meaningful. That makes sense.

MF: So you work again very closely with refugees in senior management positions you were also heading our Washington office for some time. You were leading the Bureau for Europe. Now you are working as special envoy for UNHCR for the central Mediterranean situation. People are still fleeing the wars that are not being prevented or stopped. And others are leaving because of very compelling economic reasons including some of the drivers caused by climate change. They arrive in a place like Libya and some of them get stuck. Some of them are held for many many months. Some of them have actually been kidnapped. You’ve gone to Libya. You’ve gone to those detention centers you’ve met the migrants and the refugees who are being held there as somebody who himself was kidnapped. How does it make you feel to hear those stories now?

VC: 84 percent of the people in detention have told us that they have experience some form of torture. Seventy three percent of the people have witnessed killing in front of them into his detention center. I’ve not spoken to one woman who has not been raped. Not one. In those Libyan detention center. I met recently with a young man – you know you try to avoid the question “How are you today?”, because you see where they live, you can ask how is the food, but the answer to that question can be dangerous if they are not fed and they complain about the food then the guards can retaliate against them. So one guy was really silent and say well I can’t talk to you – and discreetly he removed his shirt to show marks of torture on his body. I don’t know what inflicted those marks on his body but the person had suffered a lot. And you could see that there was no way a person could communicate. He was only communicating through his body language. And you leave that place and you say what you have achieved today? Well we can bring some blankets we can bring you a bit of food but we are not changing the dynamics of those places. So it’s constant ethical dilemma. So we are criticized sometimes say “why’d you go to those detention center, by going there maybe you give encouragement to the system to continue that”. But as humanitarian our basic principle is do not harm. You know, at least bringing a bit of medicine, bringing a bit of food and all that is better than ignoring them. Because by going there we see witness of their suffering, maybe by testifying on what’s happening to them we’ll be able to change some of the politics around that.

MF: And that’s your job now and you deliver the messages the stories – you describe what you’ve seen to policymakers and politicians in Europe and around the world. Is that changing things?

VC: Well sometimes they want to hear but sometimes they want simplification. I remember once discussing with an official that got very upset with me. I said you know I saw a woman today and she looked like my mother and I would not like my mother to be in that situation. I hoped I would not like your mother to be in that situation. And I don’t know whether there were something about his mother that I didn’t know, but that guy said “You can’t compare those woman to my mother”. And I said “I’m not comparing human beings. I just said it’s not human to be in this sort of situation”. But you try sometime to look for what is going to be the argument that works with some of them. I can’t believe that they don’t have any sense of humanity. People have families, when they go back to the kids what do they tell about their job? I believe there must be a little spark of conscience somewhere and we have to try to find it. We have to try to use it to turn things around.

VC: What keeps you up at night?

VC: The people we did not save, those we left behind in difficult circumstances and that are gone today. We did not take the right decision or the circumstances the security environment did not enable us to save them. But they have faces, they have histories, these are people, people you’ve met, and you live with them.

MF: You have devoted your life in so many ways to helping refugees. And you know I know many people around the world who are doing other jobs that are not in the humanitarian field still want to do something to help. What do you suggest to people when they ask you how can I help?

VC: Well you don’t need necessarily to help just refugees. Look around your neighborhood there are many people that need help and charity starts at home some time. But I would say volunteer – there are many cause that requires volunteers and we need to take care of also the refugees in our societies and make sure that they feel welcome. Make sure that we give them a chance to start a new life and they will stay with us for a number of years or they will return back home. But we need to make sure that we give them what were lost to some extent.

MF: Vincent, thank you very much for this conversation.

MF: You’re welcome.