One of these nations - Poland - did not send a representative because the composition of its new government was not announced until too late for the conference. Therefore, a space was left for the signature of Poland, one of the original signatories of the United Nations Declaration. At the time of the conference there was no generally recognized Polish Government, but on June 28, such a government was announced and on October 15, 1945 Poland signed the Charter, thus becoming one of the original Members.

Fifty Nations, Soon to Be United

The conference itself invited four other states - the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic, the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, newly-liberated Denmark and Argentina. Thus delegates of fifty nations in all, gathered at the City of the Golden Gate, representatives of over eighty per cent of the world's population, people of every race, religion and continent; all determined to set up an organization which would preserve peace and help build a better world. They had before them the Dumbarton Oaks proposals as the agenda for the conference and, working on this basis, they had to produce a Charter acceptable to all the countries.

Delegations and Staff Number 3,500

There were 850 delegates, and their advisers and staff together with the conference secretariat brought the total to 3,500. In addition, there were more than 2,500 press, radio and newsreel representatives and observers from many societies and organizations. In all, the San Francisco Conference was not only one of the most important in history but, perhaps, the largest international gathering ever to take place. The heads of the delegations of the sponsoring countries took turns as chairman of the plenary meetings : Anthony Eden, of Britain, Edward Stettinius, of the United States, T. V. Soong, of China, and Vyacheslav Molotov, of the Soviet Union. At the later meetings, Lord Halifax deputized for Mr. Eden, V. K. Wellington Koo for T. V. Soong, and Mr Gromyko for Mr. Molotov.

Plenary meetings are, however, only the final stages at such conferences. A great deal of work has to be done in preparatory committees before a proposition reaches the full gathering in the form in which it should be voted upon. And the voting procedure at San Francisco was important. Every part of the Charter had to be and was passed by a two-thirds majority.

This is the way in which the San Francisco Conference got through its monumental work in exactly two months.

One Charter, Four Sections

The conference formed a "Steering Committee," composed of the heads of all the delegations. This committee decided all matters of major principle and policy. But, even at one member per state, the committee was 50 strong, too large for detailed work; therefore an Executive Committee of fourteen heads of delegations was chosen to prepare recommendations for the Steering Committee.

Then the proposed Charter was divided into four sections, each of which was considered by a "Commission." Commission one dealt with the general purposes of the organization, its principles, membership, the secretariat and the subject of amendments to the Charter. Commission two considered the powers and responsibilities of the General Assembly, while Commission three took up the Security Council.

Commission four worked on a draft for the Statute of the International Court of Justice.

This draft had been prepared by a 44-nation Committee of Jurists which had met in Washington in April 1945. All this sounds over-elaborate — especially when the four Commissions subdivided into twelve technical committees — but actually, it was the speediest way of ensuring the fullest discussion and securing the last ounce of agreement possible.

Clashes of Opinion

There were only ten plenary meetings of all the delegates but nearly 400 meetings of the committees at which every line and comma was hammered out. It was more than words and phrases, of course, that had to be decided upon. There were many serious clashes of opinion, divergencies of outlook and even a crisis or two, during which some observers feared that the conference might adjourn without an agreement.

There was the question, for example, of the status of "regional organizations." Many countries had their own arrangements for regional defence and mutual assistance. There was the Inter-American System, for example, and the Arab League. How were such arrangements to be related to the world organization? The conference decided to give them part in peaceful settlement and also, in certain circumstances, in enforcement measures, provided that the aims and acts of these groups accorded with the aims and purposes of the United Nations.

The League of Nations had provided machinery for the revision of treaties between members. Should the United Nations make similar provisions?

Treaties and Trusteeship

The conference finally agreed that treaties made after the formation of the United Nations should be registered with the Secretariat and published by it. As to revision, no specific mention was made although such revision may be recommended by the General Assembly in the course of investigation of any situation requiring peaceful adjustment.

The conference added a whole new chapter on the subject not covered by the Dumbarton Oaks proposals: proposals creating a system for territories placed under United Nations trusteeship. On this matter there was much debate. Should the aim of trusteeship be defined as "independence" or "self-government" for the peoples of these areas? If independence, what about areas too small ever to stand on their own legs for defence? It was finally recommended that the promotion of the progressive development of the peoples of trust territories should be directed toward "independence or self-government."

Debates and Vetoes

There was also considerable debate on the jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice and the conference decided that member nations would not be compelled to accept the Court's jurisdiction but might voluntarily declare their acceptance of compulsory jurisdiction. Likewise the question of future amendments to the Charter received much attention and finally resulted in an agreed solution.

Above all, the right of each of the "Big Five" to exercise a "veto" on action by the powerful Security Council provoked long and heated debate. At one stage the conflict of opinion on this question threatened to break up the conference. The smaller powers feared that when one of the "Big Five" menaced the peace, the Security Council would be powerless to act, while in the event of a clash between two powers not permanent members of the Security Council, the "Big Five" could act arbitrarily. They strove, therefore, to have the power of the "veto" reduced. But the great powers unanimously insisted on this provision as vital, and emphasized that the main responsibility for maintaining world peace would fall most heavily on them. Eventually the smaller powers conceded the point in the interest of setting up the world organization.

This and other vital issues were resolved only because every nation was determined to set up, if not the perfect international organization, at least the best that could possibly be made.

The Last Meeting

Thus it was that in the Opera House at San Francisco on June 25, the delegates met in full session for the last meeting. Lord Halifax presided and put the final draft of the Charter to the meeting. "This issue upon which we are about to vote," he said, "is as important as any we shall ever vote in our lifetime."

In view of the world importance of the occasion, he suggested that it would be appropriate to depart from the customary method of voting by a show of hands. Then, as the issue was put, every delegate rose and remained standing. So did everyone present, the staffs, the press and some 3000 visitors, and the hall resounded to a mighty ovation as the Chairman announced that the Charter had been passed unanimously.

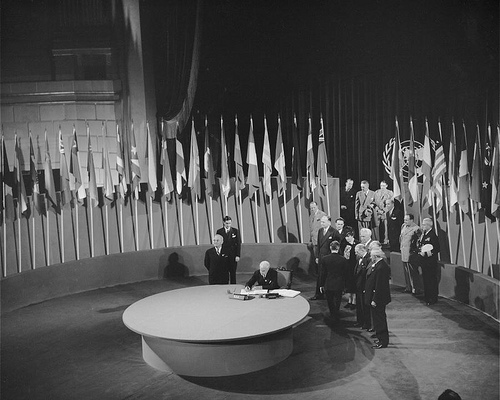

The Charter Is Signed

The next day, in the auditorium of the Veterans' Memorial Hall, the delegates filed up one by one to a huge round table on which lay the two historic volumes, the Charter and the Statute of the International Court of Justice. Behind each delegate stood the other members of the delegation against a colorful semi-circle of the flags of fifty nations. In the dazzling brilliance of powerful spotlights, each delegate affixed his signature. To China, first victim of aggression by an Axis power, fell the honour of signing first.

"The Charter of the United Nations which you have just signed," said President Truman in addressing the final session, "is a solid structure upon which we can build a better world. History will honor you for it. Between the victory in Europe and the final victory, in this most destructive of all wars, you have won a victory against war itself. . . . With this Charter the world can begin to look forward to the time when all worthy human beings may be permitted to live decently as free people."

Then the President pointed out that the Charter would work only if the peoples of the world were determined to make it work.

"If we fail to use it," he concluded, "we shall betray all those who have died so that we might meet here in freedom and safety to create it. If we seek to use it selfishly - for the advantage of any one nation or any small group of nations — we shall be equally guilty of that betrayal. "

The Charter Is Approved

The United Nations did not come into existence at the signing of the Charter. In many countries the Charter had to be approved by their congresses or parliaments. It had therefore been provided that the Charter would come into force when the Governments of China, France, Great Britain, the Soviet Union and the United States and a majority of the other signatory states had ratified it and deposited notification to this effect with the State Department of the United States. On October 24, 1945, this condition was fulfilled and the United Nations came into existence. Four years of planning and the hope of many years had materialized in an international organization designed to end war and promote peace, justice and better living for all mankind.

Related Links

- United Nations Charter

- Signed copy of the UN Charter and the Statute of the International Court of Justice

- UN Charter for Purchase

- Dag Hammarskjöld Library || 10 Documents of the First Decade of the UN

- Yearbook of the United Nations || Charter of the UN & Statute of the International Court of Justice

Video

Historical footage of the signing of the UN Charter || Documentary about the founding of the United Nations Organization and the San Francisco Conference in 1945

Extensive list of historical video footage || Documentaries pertaining to the founding of the United Nations and the San Francisco Conference

- Audiovisual Library of International Law

* click on the Video tab

Audio

United Nations Oral History || UN Charter Archives - Select interviews